Nampeyo: The Hopi Potter

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Hopi-Tewa potter Nampeyo revitalized Hopi pottery by creating a contemporary style inspired by prehistoric ceramics. Nampeyo made clay pots at a time when her people had begun using manufactured vessels, and her skill helped convert pottery-making from a utilitarian process to an art form.

Table of Contents

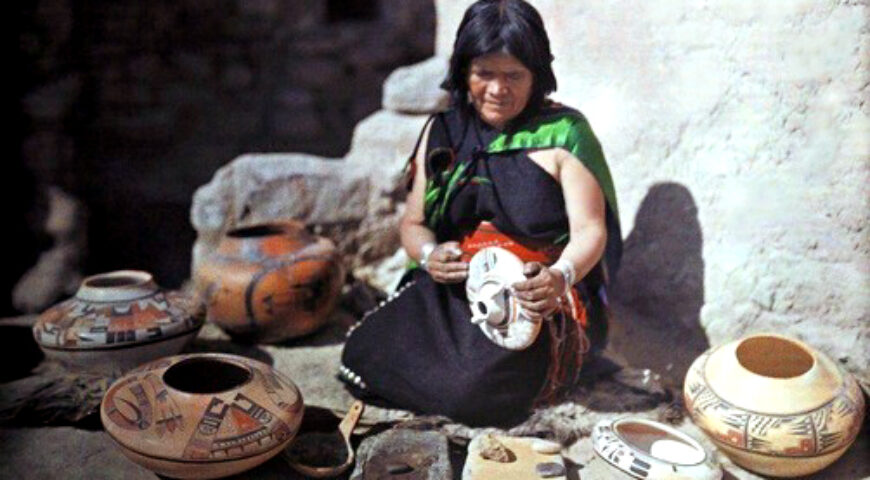

Nampeyo with one of her Sikyátki Revival vessels, ca. 1908–1910. Hopi, Arizona. Photo by Charles M. Wood. P07128

via The National Museum of the American Indian

Nampeyo, from the Hopi village of Hano on First Mesa, was born around 1860, the daughter of Quootsva of the Hopi Snake clan and White Corn of the Tewa clan. At puberty, she was given the Tewa name “Nung-beh-yong,” usually pronounced “Nahm-pay-oh” by outsiders.

She was known as one of the finest Hopi potters, crafting beautiful pieces of pottery in the traditional Old Hopi style. When she married her second husband, who was assisting at an archaeological excavation of Sikyátki near her home village, she became interested in the ancient style of Hopi pottery. Created between the 14th and 16th centuries, the ancient style of pottery was harder and less prone to cracks that the style of pottery Nampeyo’s contemporaries were producing.

Sikyatki is the name of an enormous ancient Hopi village on the east flank of First Mesa that was abandoned about 1500. The abandonment of Sikyatki is told in Hopi oral tradition as due to a dispute with Walpi, whose descendents still reside on top of First Mesa, that resulted in the destruction of Sikyatki.

Along with her husband, Nampeyo gathered pottery shards and studied the ancient designs painted on them by her ancestors, which she incorporated into her own pottery. She used ancient methods to fire and finish the pottery, producing a smoother finished surface.

“When I first began to paint, I used to go to the ancient village and pick up pieces of pottery and copy the designs,” Nampeyo told interviewers at the time. “That is how I learned to paint. But now, I just close my eyes and see designs and I paint them.”

Nampeyo was a sought-after potter by the time she was 20 years old. She married a Tewa man named Kwivioya, but the union was short-lived.

In 1878, she married Lesou of the Cedarwood clan from Walpi. She gave birth to six children from 1884 to 1900. During this time, she also produced some of her most artistic and innovative work.

Nampeyo’s Pottery Style

via Arizona State Museum

Sikyatki polychrome, also called yellow ware, was produced from about 1325 to 1630 at Sikyatki and two other Hopi villages. It was made with fine local clay that polished to a smooth, hard surface and represented a high watermark in known Hopi pottery prior to the turn of the 20th century.

When Nampeyo began making pottery, the predominant style was what is now referred to as Polacca polychrome. Produced with coarse clay, it required a thin layer of finer clay applied to the surface, on which to paint designs. The white surface layer, or slip, often cracked over time and was not as aesthetically pleasing as the earlier, Sikyatki style.

Seeking out specific clays and the raw materials needed for color, Nampeyo preferred to shape low, wide pots with abstract, geometric designs. She did not fill her bowls with detail, but used space as an art form along with intricate brush strokes and bold splashes of color.

Decorative elements that appear on the cookware or clothing are drawn from each tribe’s unique religious beliefs or world views. When Nampeyo first began making her pots, Hopi motifs had been diluted by the influence of Spanish, Tewa or Zuni designs, most frequently “Mera,” the rain bird. Even the clay used by the Hopi potters was inferior. Nampeyo’s brilliance was not only her superior natural gifts as an artist but her ability to recognize the importance of reclaiming the long-lost Hopi symbols. At the same time, she went beyond imitation and became the inspiration for continuing generations of Hopi potters.

via suduva.com

In 1904, the Fred Harvey Co. hired architect Mary Colter to design a building at the Grand Canyon that resembled a Hopi dwelling, three stories high with pole ladders ascending to each terrace.

Native artisans were invited to Hopi House to demonstrate their crafts of weaving, basketry, jewelry, and pottery-making, and to sell their products to the public. Nampeyo and her family were the first to arrive in January 1905. For three months, Nampeyo and her daughter Annie crafted pottery and were so successful they ran out of clay. Harvey employees were sent to the Hopi reservation for more materials, as Nampeyo would only use clays from certain areas.

She stayed and lived as an artist in residence at Mary Colter’s Hopi House, selling her pottery there until 1907, when she left to exhibit her works across the U.S.

Nampeyo’s daughters — Annie, Nellie, and Fannie — all became talented potters. Together with Lesou, they assisted their mother in painting her designs, especially after she began losing her eyesight in the early 1920s. Trachoma, an infectious eye disease that results in scarring of the cornea and eventual blindness, ran rampant through the Hopi Nation. Brought on by poor sanitary conditions, lack of water and an abundance of flies, the only treatment available at the time was an antiseptic solution that temporarily halted the progression of the disease, but did not cure it.

On July 20, 1942, Nampeyo died in the red-roofed house below First Mesa. She had continued to shape her pots until about three years before her death.

Today, the extraordinary quality encouraged by Nampeyo continues, even as artists incorporate their own designs and many have moved in contemporary directions. The prevalence of the motifs Nampeyo reintroduced even in Southwestern pottery today stands to show how important she was to revitalizing Southwestern pottery.

sources: williamsnews.com, grandcanyontrust.org, tucson.com, suduva.com, statemuseum.arizona.edu, cowboysindians.com, encyclopedia.com, uapress.arizona.edu, bowers.org